Somewhere along the way, dark mode stopped being a thoughtful accessibility option and became a design religion. In fact our obsession with dark mode might be UX poison disguised as user preference.

A few years ago, it was a nifty little toggle buried in your app’s settings menu. Now? It’s the default in half the web’s trendy products, a marketing bullet point, and—let’s be honest—the tech world’s equivalent of slapping a distressed font on your coffee shop chalkboard to signal you’re “cool.”

But here’s the problem: dark mode might be doing more harm than good—not just for users’ eyes, but for your product’s UX. And like Comic Sans in the late 90s, it’s being pushed far beyond the niche it was meant to serve.

The Myth of “Better for Your Eyes”

One of dark mode’s most persistent selling points is the claim that it’s easier on the eyes. And yes—in certain contexts (low light, AMOLED screens, specific eye conditions), that’s true. But the blanket statement that “dark mode reduces eye strain” is about as scientifically airtight as “Comic Sans improves literacy.”

In fact, light text on dark backgrounds can actually increase visual fatigue for long-form reading. Your pupils dilate to take in the darker background, which reduces depth of field and makes text edges blurrier. That’s why reading a novel in dark mode often feels like staring into a foggy fish tank.

If you’ve ever found yourself switching back to light mode halfway through an article, you’ve already experienced this. The irony? Designers keep implementing it because it’s “user friendly,” without considering that most users’ eyeballs don’t care about your aesthetic moodboard.

Accessibility ≠ Trend

Here’s the kicker: dark mode was originally about accessibility—helping users with photophobia, certain migraines, or vision impairments. It wasn’t meant to be a blanket style statement.

Now, we’ve flipped the script. Products launch only in dark mode because “it looks cooler,” which is like building a wheelchair ramp and then forcing everyone to use it, even if they can take the stairs faster and more comfortably. The people who actually need dark mode end up with a UX cluttered by designers trying to make it “vibe.”

And don’t even get me started on the “midnight navy” backgrounds that look sleek in your Figma file but test like garbage for contrast accessibility.

The Aesthetic Trap

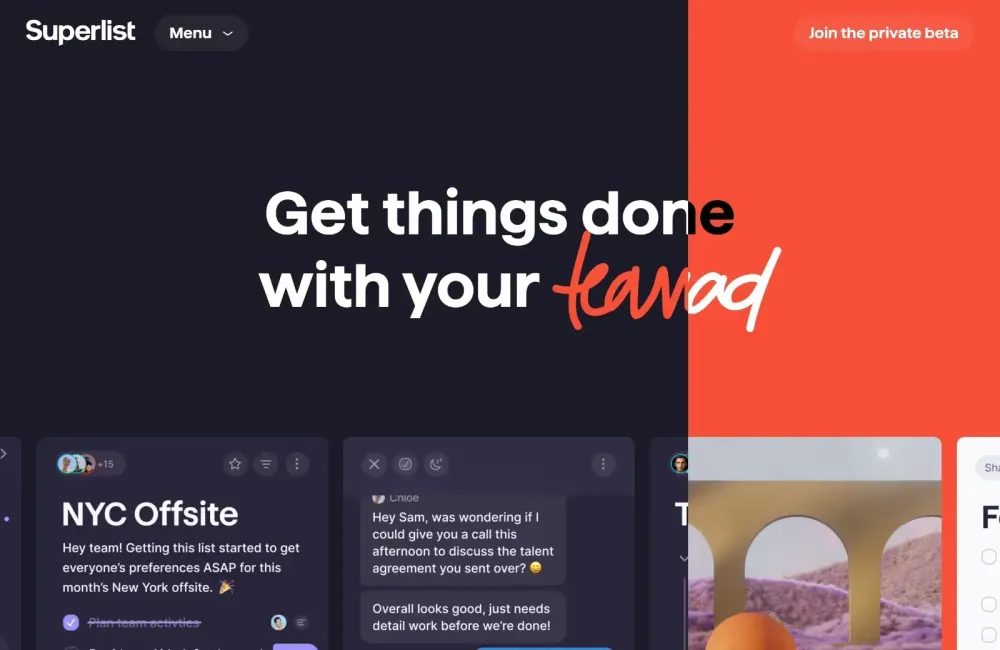

Let’s be real: dark mode sells because it looks like the future. Your landing page instantly feels more premium. Screenshots in the App Store pop. That deep charcoal backdrop says “we care about design” in a way white backgrounds never will.

The problem? The aesthetic halo blinds us to practical flaws:

- Color-coded states (success = green, error = red) lose clarity when saturation drops against dark backgrounds.

- Typography adjustments often get neglected, so your “light mode” type scale looks cramped and muddy in dark mode.

- Gradients and shadows—two of the most abused design trends—are harder to control on dark canvases without creating visual noise.

It’s the same trap Comic Sans fell into. It was fun, different, and charming—until we saw it slapped on every PowerPoint, funeral program, and dentist’s sign. Overuse turns novelty into noise.

When Dark Mode Becomes Design Tyranny

Here’s where it gets dangerous: the option to choose between light and dark has, in many products, been replaced by a design decree. There’s a growing crop of apps and websites that ship only with dark mode.

This isn’t innovation—it’s design monoculture. And monocultures are fragile. They ignore edge cases, alienate segments of your audience, and remove the very flexibility that made the feature appealing in the first place.

When we force a visual style in the name of “progress,” we stop designing for humans and start designing for Dribbble likes.

How to Avoid the Dark Mode Death Spiral

If you’re a designer or PM reading this, here’s your reality check:

- Stop assuming preference equals performance. Just because users say they like dark mode doesn’t mean they useit effectively.

- Test for actual usability, not just aesthetics. That means measuring reading speed, error rates, and comprehension—light vs. dark.

- Offer both modes—and make the toggle obvious. Don’t bury it in Settings > Advanced > Appearance > Display.

- Design each mode intentionally. Don’t just invert colors and call it a day. Typography, iconography, and color hierarchies need tailored adjustments.

Otherwise, you’re not offering an accessibility feature. You’re just chasing a trend.

The Uncomfortable Truth

The worship of dark mode is starting to feel eerily familiar. Like Comic Sans, it began with good intentions, offered genuine value in the right contexts, and then spiraled into overuse and misuse.

The real problem isn’t dark mode itself—it’s our tendency to treat design trends like religion. Once a feature gets an aura of “this is the right way to design,” we stop questioning it. We stop testing. And worst of all, we stop listening to the users whose needs don’t align with the aesthetic du jour.

Dark mode isn’t the villain. Neither was Comic Sans. But when you make a tool into a default, you’re not designing for the user—you’re designing for yourself. And that’s the first step toward UX poison.